A Note from the publisher

We’re living in an unprecedented moment in history, and it’s been amazing to see how people are pulling together to support one another. Here at TouchWood we’ve decided to ask our authors what has been keeping them busy during a time when we’ve all been asked to stay home to Flatten the Curve.

The First Five Days with Katie Bickell

A strange thing about the Coronavirus Pandemic is that, depending on circumstance, everyone experiences it on a different timeline. For a medical specialist, Day One might be the first reported case. For someone else, Day One is when they begin quarantine, or maybe when a test result comes back positive. When TouchWood Editions invited me to be a part of their Authors at Home blog series, I decided to start at my own Day One: the day after Alberta’s schools closed.

Monday, March 16, 2020

Like most days, on our Day One, I wake early to write. I complete the final edits of my first book, Always Brave, Sometimes Kind, slated for publication through TouchWood Editions this September, and then I dress, telling myself that this break from teaching preschool will at least give me extra time to write my second book, due to be submitted to the Alberta Foundation of the Arts, as per grant-funding terms, in October. Once ready to begin the day, I put on the kettle and soon the kitchen fills with my family.

Eight AM is late for our daughters to wake up. The evening before, when we learned schools were shut down, Freddy and I let them stay up until ten o’clock and we shared a meal of goat cheese, raw veggies and yogurt dip, sliced apples, pickles, kalamata olives, homemade bread with olive oil and balsamic vinegar. It was a “grown-up” snack, to be sure, but we’d put off the week’s grocery shopping to avoid panic-buyers and I didn’t want to break into any of our pantry’s non-perishables, just in case. We dined at the coffee table by the light of a single candle and the glow of the television set, a Disney movie quietly ignored.

Reflecting the flickers of light at our centre, Chloe’s eyes lit up as she gazed upon the food. “Our life is so different now,” she whispered.

“No, kid,” I laughed. “You just haven’t had a charcuterie board before.”

The day before, both girls had cried. This morning, Chloe (eight) is excited, but Cailena (eleven) is still upset.

“Did they say when we can go back yet?”

I tell my eldest I’m sorry. No news. “Nobody knows.”

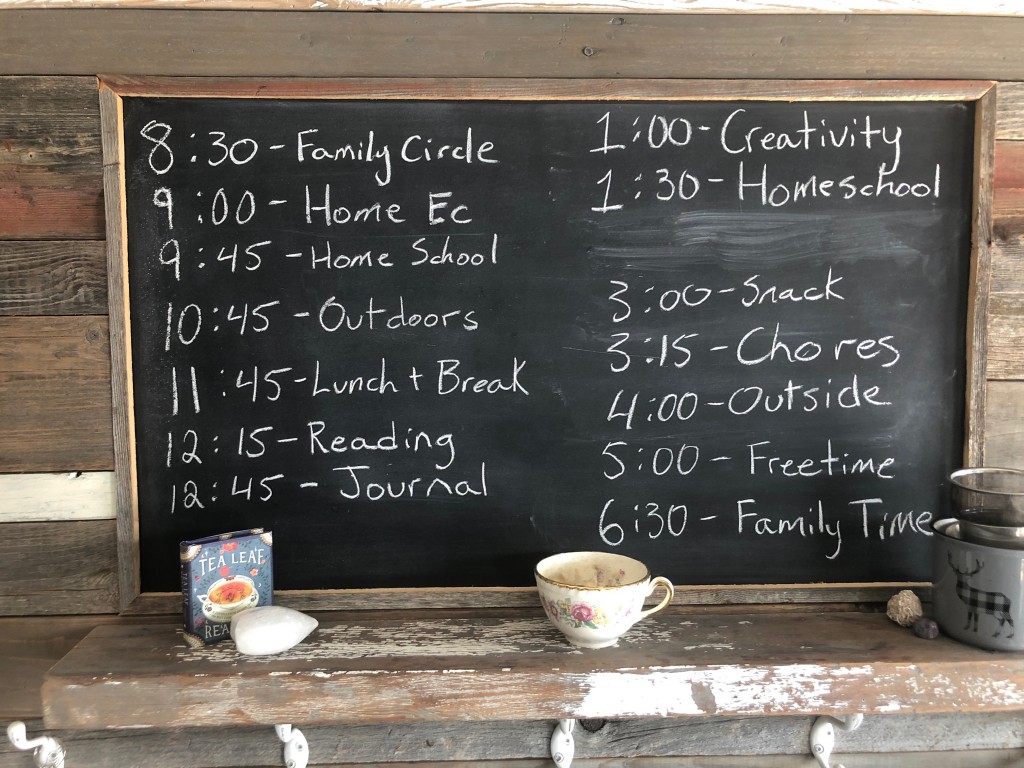

“Oh.” She stirs brown sugar into porridge but doesn’t stare into the bowl for long. On the kitchen chalkboard, a new schedule is written where we usually display poetry.

“You’re going to do all these things with us?” Cailena asks. “Every day?”

“Every day except weekends,” I say, and nod. “It’ll be like we’re in school together!” I’d stayed up after they went to bed, adapting my now-defunct preschool plans to meet the more sophisticated needs of elementary students, scared that if I don’t keep a routine I’ll let the time turn into one long weekend, each of us on separate devices in separate rooms, each of us lonely and depressed, addicted to our iPhone screens.

“I’m not calling you Ms. Katie,” Chloe jokes.

“Well, I’m not calling you Captain Underpants,” I joke back.

“Wait a second.” Cailena squints at the board. “It says: ‘two o’clock: read to the tomatoes.’ I’m not going to read to the tomatoes!”

I laugh. “Your dad made me add that one.” The pride of his garden, Freddy’s tomatoes produce such a yield we eat their canned sauces deep into winter. Sowed in February, his seedlings are now three inches tall and painstakingly cared for. Cailena mock-scowls and rubs out the line.

At family circle, the girls and I talk about what we do know: this virus usually doesn’t make children very sick, but we will self-isolate in order to protect the more vulnerable in our community and to support Dad, who will continue work his work as a firefighter paramedic. There will be no food shortages. Grocery stores are already restocking, Mom can cook anything, and Dad filled the freezer with venison that fall. Yes, the illness can seriously affect adults, but their parents are young and healthy. The kids’ greatest responsibility is to be good to one another. A lot of patience, generosity, and love will be needed over the next few days, weeks, or months.

At family circle, the girls and I talk about what we do know: this virus usually doesn’t make children very sick, but we will self-isolate in order to protect the more vulnerable in our community and to support Dad, who will continue work his work as a firefighter paramedic. There will be no food shortages. Grocery stores are already restocking, Mom can cook anything, and Dad filled the freezer with venison that fall. Yes, the illness can seriously affect adults, but their parents are young and healthy. The kids’ greatest responsibility is to be good to one another. A lot of patience, generosity, and love will be needed over the next few days, weeks, or months.

“It’s kind of like we have to be warriors,” Chloe says.

“It’s like in the war,” Cailena adds, “how everyone had a different job, but they were all important: being a soldier, or working in the factories, or knitting socks, or feeding the poor.”

“Except all we have to do is stay home and be kind,” I say, mostly to reassure myself. “Do you think we can we do that?”

Both nod.

“So… we got this?”

“We got this!” Chloe shouts.

“We got this!” I cheer in reply. “Caily?”

My eldest groans.

“We got this, Caily!” Chloe demands. “You have say it too!”

Cailena looks at me. “I don’t want to fall behind.”

“You won’t. I’ll help you.”

Our eyes lock. It’s a promise. Please? I mouth.

She shakes her head, but smiles. “We got this.”

And so, our first day begins. We bake bread and freeze mashed potatoes and the girls write recipes detailing how they did such things. We set up home-school stations and sharpen dull pencils. We dig out scribblers, tear out used pages, start journals. We top bird feeders and chickadees return to our yard. We dust off the GT Toboggan and take it to a nearby hill. Walking, we see two women chatting, one calling from behind the bug screen of an upstairs window to her neighbour on the street below, the first in quarantine from a recent trip abroad. A cheery image of a surreal time.

I check in with our fire department’s family resource group and we organize lists of people available to help grocery shop for quarantined families; we offer childcare to those among us whose families are made up of only first responders. I teach the girls how to sort, wash, and dry laundry and we laugh how folding king-sized sheets is a bit like an old-fashioned dance: together, apart; together apart, to the left, and now the corners kiss! My publisher, Taryn, sends a couple drafts of book cover options and I’m so nervous I put off opening the email for a few hours, and then dance around the kitchen when I see how beautiful they are.

Later, reading Chloe’s journal, I discovered she doesn’t know the word “enjoy” is a single word. For the eight years she’s spent on this planet, she’s believed it was customary to ask someone to experience a movie or meal “in joy.” As in: here is your meal: in joy, or please, in joy: the movie. Better yet, in joy yourself! (like, get yourself into joy!). I decide her way is better than ours and that I should in-joy these days as much as possible.

Tuesday, March 17, 2020

It’s St. Patrick’s Day. As good a day as any to follow the path of my Irish ancestors, waking to find I am abruptly unemployed and ineligible for employment insurance. I cancel what expenses I can, including Chloe’s weekly piano lessons and Cailena’s soccer club enrolment. I read over yesterday’s edits one more time and then email the file.

At eight AM, I’m ready for Day Two. I drink coffee and chat with Freddy as we wait for the girls. Chloe drags herself up the stairs wearing a green silk frock I bought her at Christmas. She is sad because she and her classmates usually make leprechaun traps and eat chocolate gold coins this time of year. When she notices her mother and big sister are not wearing green, Chloe chases us around the house with pinchy fingers until we are all screaming with laughter and then I show her the green embroidery on my bra but also change into a forest-hued button-up to make her happy.  Cailena insists the avocado print on her socks counts. At family circle, we sit on the floor and bow our heads to a recording of a St. Patrick’s Day prayer that plays through my phone. The girls are embarrassed and giggle the whole way through. We are not a religious family; the prayer just met the day’s theme. But the girls are happy because their dad and even the dog, Willow, have joined in. Chloe holds one of the Labrador’s paws, Freddy holds the other. I post a photo on Instagram and my mother calls the girls her “Wee Colleens.”

Cailena insists the avocado print on her socks counts. At family circle, we sit on the floor and bow our heads to a recording of a St. Patrick’s Day prayer that plays through my phone. The girls are embarrassed and giggle the whole way through. We are not a religious family; the prayer just met the day’s theme. But the girls are happy because their dad and even the dog, Willow, have joined in. Chloe holds one of the Labrador’s paws, Freddy holds the other. I post a photo on Instagram and my mother calls the girls her “Wee Colleens.”

That afternoon, a friend texts to invite me to join her on a walk. She has visited my home more than any other person in the last ten years and yet, when she arrives, there is a moment of awkwardness.

“Should I come in?”

She half steps into the entrance way but I’m already set to go. I feel the distance of each metre we keep between us as we walk. We talk about personal finances and about the economy. What will happen after this? Will there be jobs to go back to? The conversation moves to our children: to what degree should we keep them isolated? Is there to be no playing on the street in front of the house? No visiting playgrounds? Can the older ones go for walks together, at least? She tells me that this summer she and her husband will plant a vegetable garden. It seems necessary, in times like this. I give an update on Freddy’s tomato plants. Sowed already? They’ll be huge by the time it’s warm enough to plant them outside. When our minds are finally exhausted, we become quiet to find ourselves in the middle of an urban forest. We stop as a squirrel crosses our path.

“You know,” she said, “I hear the sky is clearer in China. Maybe the Earth will use this time away to heal.”

I nod and recite a line I’d read, earlier: “What if, when this is over, we’ve become the people we always wanted to be?”

There is hope.

When it is time to part, we don’t hug goodbye.

Wednesday, March 18, 2020

Today, consistency goes out the window. I make a mess of family circle, interrupting our new mindfulness practice to listen to Prime Minister Trudeau’s update of financial aid for those affected by the pandemic. It sounds like there are lots of options, but further research yields nothing. My situation might be eligible for the new Benefit Support program, but information on the initiative reads vague and noncommittal and won’t be fully available until sometime in April. My husband and I exchange a look. Last week we put down a deposit for orthodontic services Cailena has not yet received, and now offices are closed. Well, ain’t that a kick in the teeth?

Cailena tells us we need to skip home economics today in order to pick up their belongings at the school—news she’d read on Google Classroom. Yes, I received an email about that, I tell her, but do we really need to go? She didn’t leave anything valuable in her desk, nothing we couldn’t do without until later.

“There is no later,” she tells me. “Our desks and lockers have been cleaned out. If we don’t pick up our stuff, they’ll throw it out.”

“Oh,” I say.

“I don’t think we’re going back to school this year.”

I think she might be right.

On the drive to school I consider publications I could pitch articles to. I have a few short stories kicking around that I could sell. Or maybe I could start up my family day home again, like when Cailena was a baby…but no. Social distancing, remember? I can’t bring little kids into the house of a first responder. They’d get him sick, or he them. Freddy wouldn’t be able to sleep off night shifts and then how would he stay healthy enough to recover from the virus, or even from the exhaustion that’s every bit as sure to eventually hit? A pop song plays on the radio, an anthem about strength, about community. I think, for just a few moments, about all the worries I have that are too awful to type or speak out loud. The girls and I sing at the top of our lungs until my voice breaks and then I stop because the music is going to make me cry.

We park in front of the school. A sign points to a side door instead of the main entrance, where one of a gymnasium’s double doors is propped open. A table is set up behind the open door, blocking students and parents from entering. A school secretary wrapped in blankets and winter clothes mans the table. It’s a cold day to sit for so long. She begins to cry when she sees Cailena, who will leave this school for junior high in the fall.

“I’m sorry,” the woman says, hiding her eyes. “All my grade sixers, they’re breaking my heart.”

I let the tears welling in my eyes fall, too, and put my hands on the back of my daughter’s.

“It’s okay,” I tell her. “It’s okay for children to see adults cry when things are sad.”

At home, Chloe and I prepare a video to send to my own students. I don’t say it to her or to them, but I know it’s probably my goodbye. Most of them will start kindergarten in the fall. I don’t have it in me to read them a story, so Chloe does instead, and then we sing them a song while she plays the tune on the piano.

“I hope you are cuddled up with your favourite adult,” I tell my little preschoolers. “I hope you read a million books.”

Later, the girls and I go for a walk. On the first day, Chloe chose our walking route. On the second day, Cailena. Now it’s my turn, but neither want the exercise. I walk ahead and tell them every time they snap at one another I will lead us farther away from home. They groan and call complaints out after me. They kick ice chunks from snowbanks, push one another, cut each other off. We end up deep into a wooded trail and count six bird nests woven high above our heads. Finally, our moods lighten. We take turns climbing a tree.

Thursday, March 19, 2020

I wake early to write but instead spend the hours reading everything on the internet about COVID-19, Europe’s enforced lockdowns, Alberta’s first death, Canada’s tenth. Albertan students will be taught through distance learning, but—as far as I understand—Chloe’s classes will only cover language arts and math; Cailena the same, but with some science and social studies thrown in. I get lost down a Pinterest rabbit hole after searching “how to teach home school” and then decide to check in with a co-worker instead.

“Wash your hands,” I text when it’s time to say goodbye. “In dystopia Canada, that means ‘I love you.’”

It’s very cold today. Freddy wants to transplant the tomato seedlings into larger pots, but the bagged soil is frozen solid. He brings it into the house for a few hours to warm up, but still needs to thaw the cold, black earth with his hands as he breaks it apart, filling up the new containers. He moves the seedlings into their new home and immediately regrets the decision. The tomato plants wilt, their leaves turning almost purple, stems bent so far over their heads rest against the soil. I suggest giving them warm water, but he’s already tried that.

“Well, this always happens when we transplant,” I tell him. “It’s always a shock at first. They’ll bounce back.”

He’s not so sure. “I should have waited.”

The children and I skip our walk, skip family circle; we skip home economics, too. We spend the morning downloading educational apps. We discover Facebook Messenger Kids and the girls blow up the phones of every adult and child they’re connected to. I tell myself I should write now, while they’re busy, but it feels like so much pressure. My mind spins with questions: What if the school closures don’t last as long as predicted and I’m called back to work right away, having squandered away this writing time? What if I have to return to the childcare centre before the public schools reopen—in that case, who will take care of our kids? What if the social-distancing policies last much longer than we think—how long will I go without income? Will I even have a job to return to when this is over? Maybe I should pitch articles instead of working on the book, I think; maybe I should try make some money. Or, I could do something a little easier and tie up loose ends; finally write the dedication and acknowledgements pages for Always Brave, Sometimes Kind. Paralyzed by choice, I vacuum under the basement couches and the hallway rugs and wash my doors with warm water and peppermint oil. By the time Freddy returns home from work my mind is too busy to hold a conversation.

“You look like you’re in a trance,” he says.

I take a twenty-minute nap.

At supper, we each answer the four questions Chloe asks us without fail each night: what was one good thing that happened today, what was one bad, what are you grateful for, what do you look forward to? We all struggle with the last one. Finally, Freddy says he looks forward to fishing from his small boat in the summertime. Cailena says she looks forward to school starting again in September. I feel gutted that the things they look forward to are so far away, but I can relate—the only thing I feel positive about right now is the shower I’ll take before bed. Guilt creeps in. Am I failing us? What happened to the in-joying and the consistency I promised I’d show? The routines I know they need to thrive and grow? But then Chloe says she is excited about the Harry Potter chapter we’ll read in her bed later that night and I remember hopefulness is a group effort. We’ll take turns keeping one another afloat.

After the story, when the house is dark and quiet, I touch each tiny, fallen tomato seedling, and whisper that everything will be alright.

Please, keep growing.

Friday, march 20, 2020

It’s warmer now. Chloe has an idea, so the girls and I stuff our jacket pockets with coloured chalk and write messages on the sidewalks we travel: Hang in There! We Love You! We’re All In This Together! Cailena says we should write a new one each day school is closed. The next day, we’ll chip ice from the sidewalk in front of our house and dig out our longboards and scooters— make it springtime whether the sun’s ready to join us or not. I close my eyes and raise my face to the sun. It feels ready to come back, though, really, it was never gone.

After our walk, the kids follow online recipes to make chocolate pancakes and banana smoothies. I try to slow down, to rest, to be the peace I want for this home. I play music, water houseplants, toss a handful of seeds out to the chickadees. Chloe and I have a few rounds of Go Fish. Cailena’s grade six class meets in video conference and when I accidentally barge into her room to deliver clean laundry, she flatters me by inviting me on-screen. “Look guys! It’s my mom!”

Chloe spends an hour on Facebook Messenger reconnecting with my little brother who lives far away but is a musician, like her. They talk about music and I make a mental note to ask him about giving her a few piano lessons through Messenger. Eventually, the girls abandon their tech to play in the backyard. Laughter rings through the kitchen window as they chase each other around in the snow, climb over the swing set, crawl through Willow’s doghouse. I think of when they were very little and used to play that same way, before they each made their own friends down the street and stopped spending so much time together. It’s nice, like something of a second chance, like a rerun of early sisterhood that ended so, so soon. I’m grateful for this day. I’m looking forward to another.

I sit to write and actually make headway, not on the book but, at least, on this article. I ask Chloe to take a photo of me at my desk so I have an image of myself to include. I consider what excerpt from Always Brave, Sometimes Kind I’ll include: something meaningful, something encouraging, something about the trust we keep when travelling into the unknown. So, again, I read through many passages. The book is full of symbols: flowers, the moon, tides, the seasons. Everything in flux has a healing way about it, I think, and yet the only consistency about these things is that they are simply there.

And me, too, I realize, that’s all I have to be. For my girls, for our family, for this world. The only thing most of us have to be is, simply, here. Trying our best, being good to one another, taking turns keeping each other afloat. In the windowsill, the tomato seedlings recover from their shock and lift their heads, strong and brave.

Hope is a group effort.

Besides, we can try again on Monday: Day Eight.

“Faith”

excerpted: Always Brave, Sometimes Kinds

Snow flies in the dark outside Jim’s windshield like he’s crashing through space and dodging asteroids, a suicide mission at warp speed. Nothing or anything could lay beyond the metre of coned illumination his headlight’s cast: deer, moose, oncoming vehicles. Jim grips the wheel. A few weeks ago, a trucker was left nearly dead on this same road. A girl he’d picked up convinced the man to turn onto a range road where her boyfriend was waiting. But what are the chances of two people getting hurt on the same road? Not so likely. Except, of course, they never did find the girl. The chances of the same person hurting someone twice? Jim checks his passenger out the corner of his eye. Well, that’s a different story.

A chill runs over Jim’s arms.

No. He shouldn’t make assumptions. God knows enough are made about riggers like him. Gentler folk believe all oil workers to be hurtin’ Albertan cokeheads screwing desperate women in oilfield housing; swimming in the big bucks while the wives at home spend it on Escalades, Prada bags, and antibiotics for reoccurring venereal diseases. That’s the joke. And maybe Jim’s met a few shitheads like that but, truth is, most of the guys he knows are just so damn tired, just so damn homesick, just so damn determined their kids won’t do without in a province with a cost of living so high it’s near impossible for a man to make a living.

“So where you going?” Jim asks the hitchhiker.

“Truck stop.”

“No, I mean, are you catching the bus? You from the city?”

The girl shrugs. “Just waiting to see what turns up, I guess. See who’s around.”

Jim nods. He’s heard the crew laugh about the women who work truck-stop parking lots.

“How much did your truck cost?” the girl asks. Jim looks over as she plays with the truck’s buttons and dials. Under the centre interior light, he can see thin blue veins under her skin of her neck, the track marks on her inner arm.

The muscles in Jim’s shoulders tense. “Why?”

“Just wonderin’.” She leans over the centre console to read his dash. “Looks like you need to gas up, anyway. I know a real private spot if you wanna hang out.”

Jim shakes his head. “I got family waiting at home.”

“Shit,” she laughs. “Who doesn’t?”

He stares straight ahead and they drive a little longer in silence. Light reflects off a Curve Ahead road sign and Jim slows down, unsure where the bend is without road lines, asphalt, or even tires marks visible in the fresh powder. He follows the thinning patches of grass, only visible where the shoulder shelters the sparse blades.

“Does anyone know you’re out here?” Jim asks the girl, “Do you have a phone? Any way to protect yourself?”

“Who do I have to protect myself from, man?” She laughs and takes out a small pocketknife, flipping the blade to clean under her nails. “Little things can do a lot of damage, you know?”

Jim tries not to swallow. “I’d feel better if you put that away.”

The girl cocks her head and smiles at him.

“Yeah, I bet you would.” She stares a minute longer and then shakes her head. She slips the knife back into the pocket of her coat and laughs.

“Man, you gotta have a little faith, you know?”

Jim pulls into the truck stop parking lot and parks alongside the gas pump.

“You sure you don’t want to hang out?” the girl tries again. “It don’t cost too much.” Lit up by the overhead light he sees the gap in her front teeth, so wide it’s like she’s missing a pair. She’s younger than he thought; blue eyes shining like all the world’s still new and exciting, like she hasn’t done what’s she’s going to do near long enough to know any better about it.

Jim shakes his head.

“Listen,” he says. “Whatever you’ve got to do to be safe, just do it, okay? Don’t even hesitate. You be safe, and I’ll get me some faith.”

The girl’s smile fades. “Yes, sir,” she whispers.

She leaves out the passenger side door and Jim watches her walk to the truck stop’s front entrance as he fills his tank at the pay-as-you-pump. She turns and flashes him a peace sign. Jim nods in return.

Snow-blind, he thinks of faith as he pulls back onto the highway: faith in people; faith in the patch; faith in two people trying to hold their world together; faith that the road will be clear. Faith that doing the right thing won’t hurt too bad, or maybe that it just won’t hurt too bad for too long. Faith to keep on keeping on, because there isn’t any other way, or faith that whatever happens is meant to happen, whether a person likes it or not.

450K to Edmonton, a road sign reads.

He reaches into the cup holder to let his wife know how long until he’s home but the phone’s not there.

He thinks of the girl, just that little bit safer.

A consequence of faith, Jim thinks.

One he can live with.

Excerpted and condensed from Always Brave, Sometimes Kind by Katie Bickell (forthcoming fall 2020). Find more information here