A Note from the publisher

We’re living in an unprecedented moment in history, and it’s been amazing to see how people are pulling together to support one another. Here at TouchWood we’ve decided to ask our authors what has been keeping them busy during a time when we’ve all been asked to stay home to Flatten the Curve.

Meet Michael

Hello, everyone! I am Michael Layland. So far, the dreaded virus has not affected my writing life all that much. I have been working at home for a few years now, and have established a comfortable rhythm, spending a couple of hours at a time at the computer, then taking short breaks to stretch the legs and little grey cells.

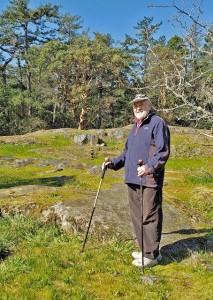

I make a point of taking advantage of the location of our home which is close to some rocky woodlands that never fail to show me something of interest. Today, I saw the first of the fawn lilies open. All the bird life is now in full song, with the bass line provided by a family of ravens. When we first came here, some 30 years ago, I started to list the species of birds I saw in these woods, and on and over our nearby seashore. I reached 125 within a few years, but then stopped counting. By now, I would guess, my local list would be at least a dozen more. I still keep an eye out but am not obsessive about it, just thankful to live in and enjoy such a rich and varied micro-environment.

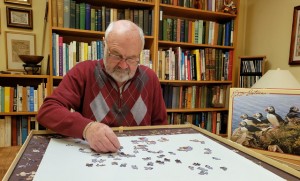

I have also spent time in deep concentration over a tricky jigsaw of a painting of horned puffins by Robert Bateman. I’ll not be finishing it as it takes too much time away from my writing. My dear wife (and editorial advisor), Jean, took both pictures. She, too, has a book in the works, about which I’m not encouraged to comment!

The shut-down of all public facilities such as the libraries and BC Archives would have hindered research for my writing — I estimate that about 25 percent of my time on each book is related to research, 10 percent to planning and scoping, 25 percent to actual writing, revising, pruning, and tweaking, 20 percent spent on selecting the illustrations, 10 percent on end-matter such as endnotes and references, and the remaining 10 percent in discussion with Taryn, my publisher, and her wonderful team of designers, checkers, and marketers. Where was I? Ah, yes: impact of the closures. Very fortunately, for my fourth book, I had already done much of the research that needed such access. I have assembled most of what I need to start writing.

This book will be a departure from the series that I have just completed. It is the biography of a chap, a British naval officer, who first came to Vancouver Island in 1857. He then went on to a roller-coaster of a life, here and during world-wide travels, that included seeing the Cariboo gold rush from a vantage at the lowest level, British Columbian politics during their most tumultuous years, and the upper echelon of the Raj in India. This is a yarn as yet untold, but one that deserves to be known. My working title is “Never say Die!” a motto he learned young, and lived by.

So, all in all, Jean and I feel that we will be able to weather this storm. We are taking all the recommended precautions and have the internal resources to withstand the relative isolation with patience and good spirits. We wish all those connected with TouchWood (what a great handle, for these times!) and the Heritage Group generally, all the very best of fortune and health over the next testing period and for the future.

Women in Botany

Excerpted: In Nature’s Realm

In the late 17th century and through most of the 18th and 19th centuries, gentlemen in British society were permitted, and admired for, active participation as serious amateurs in science and most of the fields of natural history. The same courtesy, however, was not extended to women. Members of the learned societies were almost exclusively male.

In the late 17th century and through most of the 18th and 19th centuries, gentlemen in British society were permitted, and admired for, active participation as serious amateurs in science and most of the fields of natural history. The same courtesy, however, was not extended to women. Members of the learned societies were almost exclusively male.

Only botany was an exception to this societal discouragement of women in science. It was considered quite acceptable for respectable ladies to take an active interest in their gardens and conservatories, in wildflowers, and even in seeking out new species away from their homes. Painting floral subjects was viewed as a most becoming accomplishment for a well-educated young lady. Botany also resonated with society’s perception of women as being knowledgeable about edible and medicinal plants.

. . .

Emily Henrietta Woods

One of three women artists who lived in Victoria (and were coincidentally named Emily), Emily Woods was born in Parsonstown, Ireland, in 1852. When she was just 13, her family came as settlers to Vancouver Island. Her father, Richard, soon obtained a senior administrative position at the Supreme Court, and the family set up a comfortable home, “Garbally,” on the Victoria Arm waterway, just outside Victoria’s city limits. Emily’s parents could afford to send her to the exclusive Angela College, where she took lessons in drawing and watercolour that revealed her considerable artistic talent.

Her particular love was for the wildflowers that surrounded the Garbally property, and she devoted her life to finding and painting plants, travelling throughout the province to do so. The accuracy of her work shows her keen interest in botany. She usually provided both common and scientific names for the plants, and in some cases she also noted how the Indigenous Peoples made use of them. In 1884, one of her pen-and-ink sketches won a first prize at the annual provincial exhibition.

During her time at the college she met two sisters, Edith and Clara Carr, who also shared her art lessons. Later, Emily gave drawing and painting instruction at some small elementary schools. At one of these, a younger sister of her friends from Angela College took her first art lessons. This was Emily Carr, who later wrote:

I was allowed to take drawing lessons at a little private school which I attended. [This would have been Mrs. Frazer’s at Marifield cottage. Carr called it “the, nicest school I ever went to” in the essay “Mint” in her book Wild Flowers.] Miss Emily Woods came every Monday with a portfolio of copies under her arm. I got a prize for copying a boy with a rabbit. Bessie Nutthall nearly won because her drawing was neat and clean, but my rabbit and boy were better drawn.

Emily Woods never married. For a while, she taught at St. John’s church and participated in various patriotic and charitable associations. In later years, she shared a home on Bourchier Street with her unmarried sister, Elizabeth Ann. Emily died from cancer in 1916. During her life she produced more than 200 watercolours of flowers, or flowering shrubs and trees, and some 50 landscapes or scenes. The BC Archives holds four albums of her work. In 2005, the Royal BC Museum published Kathryn Bridge’s compilation of charming vignettes written late in life by Emily Carr, each devoted to one plant, and exquisitely illustrated with an Emily Woods watercolour.