A Note from the publisher

We’re living in an unprecedented moment in history, and it’s been amazing to see how people are pulling together to support one another. Here at TouchWood we’ve decided to ask our authors what has been keeping them busy during a time when we’ve all been asked to stay home to Flatten the Curve.

Meet Leesa

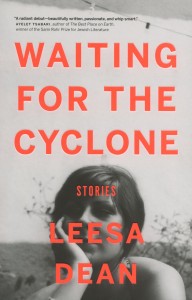

Hi! I’m Leesa Dean, author of Waiting for the Cyclone as well as the poetry chapbook The Desert of Itabira (2020, above/ground press). I teach Creative Writing at Selkirk College and live on an acreage in Krestova, a rowdy little hamlet located in the West Kootenay region of BC between Nelson and Castlegar.

I landed in Krestova three years ago after 16 years of moving often, sometimes clear across the country, other times for seasonal jobs, making a home in cabins and tents. Once, I land-travelled to Nicaragua and back over the course of a year, which included a 5,000+ kilometre stint by bicycle. Even when I lived long-term in Montreal, I moved every July 1st, so to finally be in one place, especially in unstable times like these, feels really good.

Here, I live with my husband and daughter. My husband Matty Kakes is a mural artist and also an educator at Selkirk College, so we are both still hard at work in the virtual classroom and in our art practices. Our 21 month old daughter Scarlett watches all of this with her mischievous curiosity, contributing where she sees fit, swatting the keyboard as I write this and video-bombing Zoom meetings with her delightful cackle.

Quarantine has re-ordered my life. All the things I used to do still exist, but they’ve been clipped into much smaller pieces and tossed in the air to swirl out of sequence. What I mean is this: instead of working while my daughter is at daycare and doing everything else at night/on weekends, all tasks have converged—I one-finger type an email while trying to imagine an alternate ending for a problematic chapter in my new book while reading Dr. Seuss tongue twisters while ordering starters from a local Doukhobor farmer because we are suddenly obsessed with food security. Last week, we planted a field of quinoa. Will it grow? Who knows?

I actually appreciate certain aspects of this externally imposed chaos. It reminds me of grad school, the timelessness of having immense responsibilities and questionable discipline, yet still needing to get everything done. In this new, individual world order, I feel closer to my natural rhythms. I’ve always enjoyed constant change, the adrenaline of switchbacks.

Since my concept of time is already so screwed up, I’m kind of running with it. Easter lasted a week, maybe two. Actually, I was gardening in ears today—I think Easter is still happening! We have fake birthday parties, too. I’m probably closer to 60 than 40 now. I’m looking forward to a return to some kind of normalcy, though, mostly for the sake of others whose lives have been greatly disrupted. But in the meantime, I’ll be doing yoga during Zoom meetings with my camera off while my daughter tries to ride me like a horse.

I decided to provide an excerpt from “One Last Time,” a story in Waiting for the Cyclone. It’s loosely based on my mother’s death, and it begins with a woman taking a spontaneous trip to Mexico. I’ve been thinking about that story lately for two reasons: 1- I miss my mom, especially in these times of social distancing, and 2- I wonder when I’ll ever get back to Mexico?

One Last Time

Excerpted: Waiting for the Cyclone

Last February, I decided to go to Mexico because someone I barely knew died. A twenty-three-year-old musician, friend of a friend from Vancouver who I met at a party once. I thought she was so beautiful, but in a simple way that made some people look at her as plain. After I heard about her passing, how she died in her sleep for no discernible reason, I found myself watching her one and only music video on repeat. I memorized the earrings she wore, the mole on her chin, her curly hair, the space between her teeth. Knowing she was no longer in the world felt like the worst thing and I couldn’t figure out why. I guess I saw her potential to be great but knew that instead, she’d end up being forgotten.

I left three weeks later, on Valentine’s Day. The gate was populated mostly with businessmen and couples leaving for romantic holidays. I wondered how they would classify me, if they even registered my existence, and decided based on their gazes, either on their phones or on each other, that they did not. The plane left at three and I tried to hold in the nausea, ignore the high-pitched pressure in my ears as we gained altitude, tried not to think about how scared I felt, losing gravity, regretting the decision altogether.

There was a stopover in Dallas at sunset, an event everyone watched through the terminal window. The sky was all hot coals, clouds on fire, and the entire American Air crew, pilot and all, sat in a row beside me, immobilized, silent. Planes mapped the horizon, landing, hovering; the sky looked magnified and I couldn’t help but think of my mother, working at an airport all those years. She spent most of her life in the terminal café, admiring the mountains, earning a meagre wage to raise me properly, mistake that I was. Before my flight, I stopped in to kiss her goodbye and she snuck a sandwich into my carry-on. i love you, I texted before the connecting flight left Dallas. so much, she wrote back.

As we flew through the night, I flipped through my guide book to Mexico City, a used copy, dog-eared and marked according to someone else’s sensibilities. I tried to guess what kind of people they had been based on the marks and symbols—probably young backpackers. They never stayed anywhere expensive. Neither would I. Below, the full moon reflected on the water. Could the fish beneath it feel the glow?

City lights soon dotted the landscape and a quagmire of boulevards mapped the city’s sprawl. When the wheels hit the runway, the passengers around me had that look on their faces—home.