A Note from the publisher

We’re living in an unprecedented moment in history, and it’s been amazing to see how people are pulling together to support one another. Here at TouchWood we’ve decided to ask our authors what has been keeping them busy during a time when we’ve all been asked to stay home to Flatten the Curve.

Meet Ian

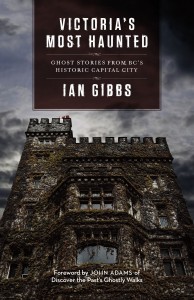

My name is Ian Gibbs. I live in Victoria, BC, and my first book, Victoria’s Most Haunted, came out a couple of years ago. Since then it’s been a lot of fun watching the seeds from the book grow, like hosting a podcast, leading ghost walks, and getting to do interviews on radio and TV—admittedly usually only at Halloween.

I am currently working from home, doing my regular day job but getting a lot of assistance from Randy Savage the Siamese cat and self-appointed lord of the manor. I’m also working on my next book. I’m really missing doing the Ghostly Walks, but thanks to the miracle of technology I am still co-hosting my bi-monthly podcast, The Ghost Story Guys, all while staying home.

I am currently working from home, doing my regular day job but getting a lot of assistance from Randy Savage the Siamese cat and self-appointed lord of the manor. I’m also working on my next book. I’m really missing doing the Ghostly Walks, but thanks to the miracle of technology I am still co-hosting my bi-monthly podcast, The Ghost Story Guys, all while staying home.

I’m trying to be smart and strategic when I need to venture out, and keep in mind all those friends who for whatever reason can’t get out and need some help or something picked up. If nothing else, I’ve noticed a lot more care in the community than I realized was there. There’s ugliness too, of course, but it’s great to see that balanced out by the goodness and kindness people are showing.

Point Ellice Bridge

Excerpted: Victoria’s Most Haunted

On May 26, 1896, the city of Victoria was celebrating Queen Victoria’s birthday. There were picnics, fairs, and, most exciting of all, a military exhibition at Macaulay Point in Esquimalt.

On May 26, 1896, the city of Victoria was celebrating Queen Victoria’s birthday. There were picnics, fairs, and, most exciting of all, a military exhibition at Macaulay Point in Esquimalt.

Getting from downtown Victoria to Macaulay Point meant hopping on the streetcar on Government Street, going a short way along Wharf Street, and then over the Point Ellice Bridge, which was built in 1885. Streetcars began going across the bridge in 1890, but the bridge was originally built for horse carts and pedestrians, not heavy streetcars. The city was aware of this. In 1892, they sent surveyors and repairman to drill holes in the bridge pilings to check the condition of the wood. They found that the wood was in bad shape and needed to be replaced, not just repaired. Four years later, nothing had been done to fix the pilings, and the holes that had been drilled in them had neither been filled nor repaired, hastening the rotting that had already begun. People continued to report that the bridge would sag whenever a streetcar went across, but those reports were ignored and the streetcars continued to cross the bridge.

At 1:40 pm on May 26, the city’s inaction finally came with a price. Car number six, one of the older, smaller, and lighter streetcars, made its way safely across the bridge. As soon as it reached the other side, streetcar number sixteen, one of the larger, heavier new cars began its crossing. The car was built to carry a maximum of fifty-five people, but was actually carrying one hundred and forty people that day. The car had gone about a quarter of the way across when the bridge began to sway. The streetcar pressed on, and the swaying increased. With a terrifying crack, the bridge dropped about half a metre. The streetcar kept going. When it reached the centre of the Point Ellice Bridge, an even louder crack was heard throughout the harbour. The centre span of the bridge broke. Streetcar number sixteen plunged into the water, landing on its side. A few moments later, the main tracks and the rest of the span fell on top of the streetcar, trapping and killing even more people, including some who had managed to survive the first part of the disaster. Some lucky ones benefitted from the rest of the bridge collapsing, because it hit the streetcar with such force that it pushed them out through the broken windows. When it fell, the streetcar landed on some of the wood and ironwork that had broken off of the bridge when it first cracked. The car was actually pierced when it landed in the water, and then debris crushed even more of the car as the rest of the bridge collapsed on top of it.

Boats that had been cruising around the harbour saw what was going on and hurried to the disaster. Many people were saved because there were so many pleasure boats sailing around due to the birthday celebration. In all, fifty-five people died in the disaster and twenty-seven were seriously injured. The rescue effort soon became a recovery mission, with bodies being laid up on the beautiful lawns of nearby homes. People used tablecloths and curtains as shrouds for the victims. It was and still is the worst streetcar disaster in North American history.

The City of Victoria and the streetcar company were both found negligent: the streetcar company for overloading the car; the city for knowing the bridge was unsafe, making it more unsafe, and doing nothing about it. The compensation they were ordered to pay rendered the streetcar company bankrupt, and the city was almost broke for the next four years. The story was in the newspapers for months; there was not a single family in Victoria that had not been affected by the tragedy.

It seems that some people still aren’t quite ready to give up looking for their loved ones lost in the disaster; they are not going to let a small consideration such as time have any bearing on whether or not they keep looking. In the 1890s, the banks of the Gorge were lined with big beautiful homes. Now, the only house left in that area is Point Ellice House. The rest of the properties lining the waterway have given way to industrial properties and warehouses. There is a path called the Galloping Goose Trail, which runs along an old rail line from downtown out to the other municipalities. Part of this trail goes under the new and improved Point Ellice Bridge, also known as the Bay Street Bridge. If you go down to the Galloping Goose Trail on a quiet night and stop just across from the old pilings from the Point Ellice Bridge, you may see proof of loved ones still searching. As you sit quietly, letting the atmosphere take you in, you will feel an eeriness surround you. If you look over to where the doomed bridge once spanned the water, you will notice something strange. Tiny lights, some yellow, some red, can be seen drifting over the surface of the water. They trail back and forth, only over one spot. Car lights do not reach that spot, nor do streetlights; it’s simply an unexplained anomaly. After the bridge fell, many people were not recovered until the next day, but through the night there were boats full of searchers going back and forth over the sunken streetcar with lanterns attached to their small boats. Many who have witnessed these lights have said that you can even hear soft sighing noises that seem to go with the lights and their motion. Are these the sighs of the rescuers slowly giving up hope? Or the sighs of the dead who congregate around you, watching their searchers, knowing there is nothing left to look for?