A Note from the publisher

We’re living in an unprecedented moment in history, and it’s been amazing to see how people are pulling together to support one another. Here at TouchWood we’ve decided to ask our authors what has been keeping them busy during a time when we’ve all been asked to stay home to Flatten the Curve.

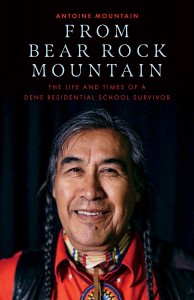

Meet Antoine

My name is Antoine Mountain, and my first book was From Bear Rock Mountain: The Life and Times of a Dene Residential School Survivor. I am a 5th Year Indigenous PhD Studies student at Trent University in Peterborough, and am now done with coursework, comprehensive exams and am about to finalize my research proposal.

- During this period of social distancing, I have been keeping myself busy doing the following:

- Reading. Currently: Crazy Horse: A Lakota Life by Kingsley M. Bray

- Working on the final draft of a new writing

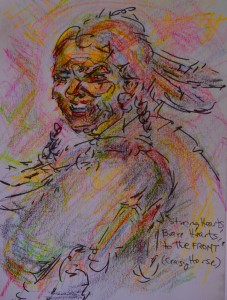

- Drawing twice a day, a habit I’ve had since 2011, and practicing my photography

I have also been participating in some Indigenous ceremonials, running Sweat Lodge Ceremonials and Sweetgrass Ceremonies.

An example of my daily sketches

In the Mountains

Excerpted: From Bear Rock Mountain

My grandparents on my mother’s side, Peter Sr. and Marie-Adele Mountain, are from the Sheetao T’ineh, the Mountain Dene. Grandfather Peter came from the Mayo region in Yukon, and we still have some relatives there. His wife, Marie-Adele, was closely related to the Tobacs. One curious fact is that, although my grandparents were quite elderly, I had uncles who were younger than me. Life there in the 1950s must have been the last of the moosehide boat days, when we would harvest moose and then go down the river and spend the summers in the fish camps.

My grandparents on my mother’s side, Peter Sr. and Marie-Adele Mountain, are from the Sheetao T’ineh, the Mountain Dene. Grandfather Peter came from the Mayo region in Yukon, and we still have some relatives there. His wife, Marie-Adele, was closely related to the Tobacs. One curious fact is that, although my grandparents were quite elderly, I had uncles who were younger than me. Life there in the 1950s must have been the last of the moosehide boat days, when we would harvest moose and then go down the river and spend the summers in the fish camps.

I recall the dog team ride up to my grandparents’ was one glorious affair with the stars visible and the clear sounds of the dog bells, those big round and shiny loogoolu, echoing off the trees and rock faces.

That high up, though, sometimes we had to walk, and that made for treacherous going. When we came to a fast-moving stream, we had to cut down a big tree for a bridge that everyone had to go over, gear and all.

Once camp was set up, there was no other place quite like the mountains to live in, with that feeling of being apart and in a separate and divine world. Everyday concerns as we knew them simply did not take on such importance.

I first saw a traditional teepee there, covered in spruce bark, I believe. It would be quite a number of years before I would see another, in, of all places, our first home about thirty thousand years ago: Siberian Russia!

Those years were also my very first recollections of having tried my hand at any kind of art. Of course, there were no such things as paper and pencil in a traditional Dene camp. My sketchpad was a simple block of spruce with a smooth enough surface, and I used pieces of coals from the fire to make my artwork. It was always a little sad for me to have to see my brilliant first works of art go into the fire! But no one said anything, and that was that.

Camp life was always busy, with everyone having a set of chores to do. My mum in particular always told us, “If you see something that needs to be done, just do it. Don’t ask anyone, just do the job.”

In that way, we learned very early to do things for ourselves that would be of use to others. There were some things you really had to watch out for, though. Some of those chores had their risks, like knives, axes, and gathering water.

The streams in that high country run much faster than down below, and I was almost swept away when I put my pail in too fast to get our drinking water. There was the roar of the rapids as they swept past our camping spot, but it becomes so much a part of daily life that you tend to forget the danger. As a young boy, your mind tends to wander to other things . . . What’s happening with the guy(s) with the guns? Maybe they’ve spotted a moose or woodland caribou or are shooting at some jolly ducks. Then, wham, you feel the sharp tug all the way up to your arm sockets, and you grab for the curved metal handle of the water bucket and almost topple right into the churning ice-cold mass headfirst before finally being able to regain control.

That sudden shock quickly took me out of my silent reverie, let me tell you! You wouldn’t want anyone to know you almost lost your life, so you’d just go back, put the water in its place by the fire, and go on with your day. Such is camp life.

Of course, being one with an artistic spirit, I was often taken away just by the deep and rich colours in this country. I was outside, as usual, very early one morning to catch that certain shade of enriched blue in the willows and trees. I had a piece of bannock, a kind of country bread fried in a large black cast-iron frying pan, which I held behind me as I gazed at these wonderful hues playing in the snow-laden bush with the dawn just breaking over the higher peaks. When bannock was still frozen, it was so good to just gnaw on outside in the cold.

But a loose dog came along and snatched my bread! So I learned to eat my food right away and not walk around with it. Then, in places like those blue willows, I could just give in to the hypnotic power of the land.

I didn’t really know what that power was then, and to this day hope I never do, but gazing at the way the snow and early morning pink dawn played against the snowy branches, I just let my eyes go unfocused. This is a kind of self-hypnosis, allowing for a super-vision of sorts, where even the most minute of sounds drops off and fades far away from our cold mountain abode with none but the morning star or a wishing moon, a new moon you can make a wish on, as a guide.

I was taken to a warm, glowing haven filled with images that slowly transformed themselves in pure imagination. I even learned to name this place—The Near Room—but not until much later in life. Some call it a vision. I didn’t know what to call it. But I did know, even then, there is a place connected with it. Our camp, being so far from anywhere, gave me the notion that it was everywhere at once.

Meanwhile, back in camp, we were making moosehide boats. It took up to fifteen green untanned moosehides to make a boat. With a spruce tree frame, a boat was big enough to carry a number of families. There would be about thirty people aboard, braving the roaring, splashing waves rushing past the boat! It was the only way to get out of there in the springtime. Those times took me all the way back to my family’s Mountain Dene roots.

As you can well imagine, it was a lot of work making those boats, especially for the girls and women who did the double and folded-over stitching to make the craft waterproof. When the boat was ready, it was indeed one glorious and adventurous ride all the way down the roaring streams to the Duhogah, far below, with a hodgepodge mass of dogs cowering in the bottom and we children squealing for joy! It was dangerous, with sharp rocks on all sides ready to rip the entire craft to pieces and drown all within. I lost uncles on these boat rides.

With all of this tragedy only the thickness of the sewn moosehide away, our elders had to make sure we stopped along the way to make offerings to the Spirits of the Mountains for our safe passage over the waters they dwelt in.

After this big adventure, life along the Big River, the Duhogah, settled to a slower pace.