Food Security Is Just a Seedling Away

By Janet Melrose and Sheryl Normandeau

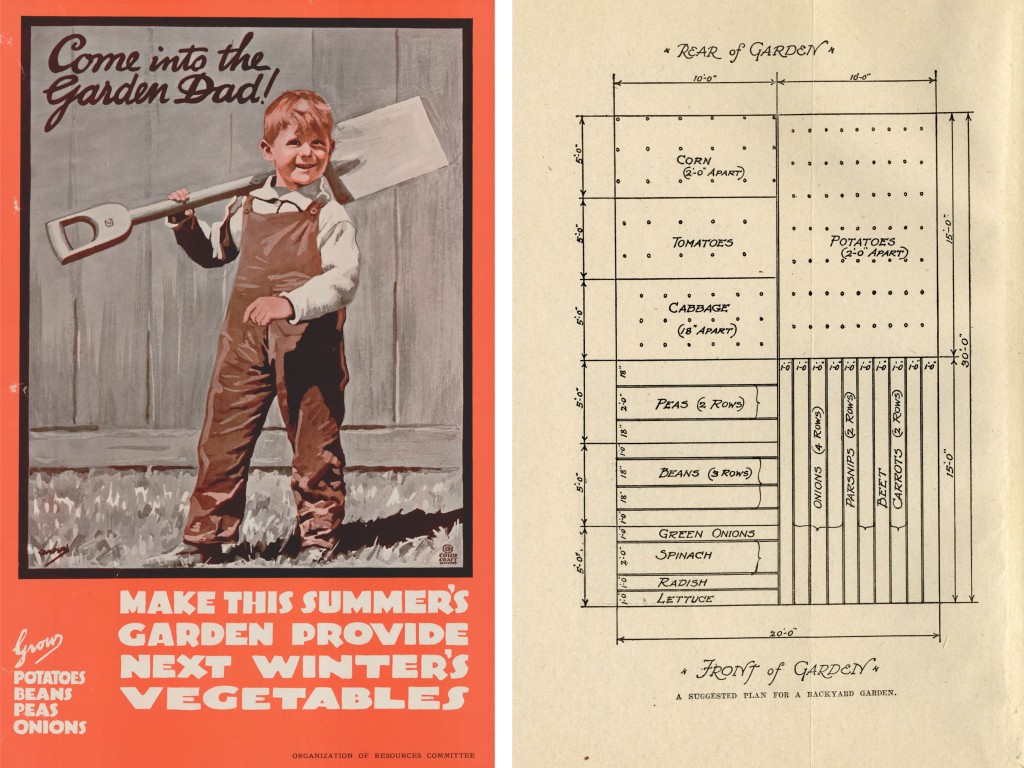

During WWI and WWII and into the 1950s, the Canadian government encouraged its citizens to grow their own food. Not only would you be supplementing your own food supply at a time when rations were scarce and store shelves were growing bare, but people who grew gardens were contributing in their own way to the war effort. Growing a “victory garden” was a patriotic duty. In a time of profound anxiety and loss, when people’s lives were on hold, gardening and growing food was both a positive action and a solace.

Fast forward to 2020 when the threat isn’t war, at least not for Canadians, but COVID-19. Shortly after the World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 a pandemic, seeds became the new toilet paper. People are interested in starting a garden for the first time, and garden centres and seed sellers have been swamped!

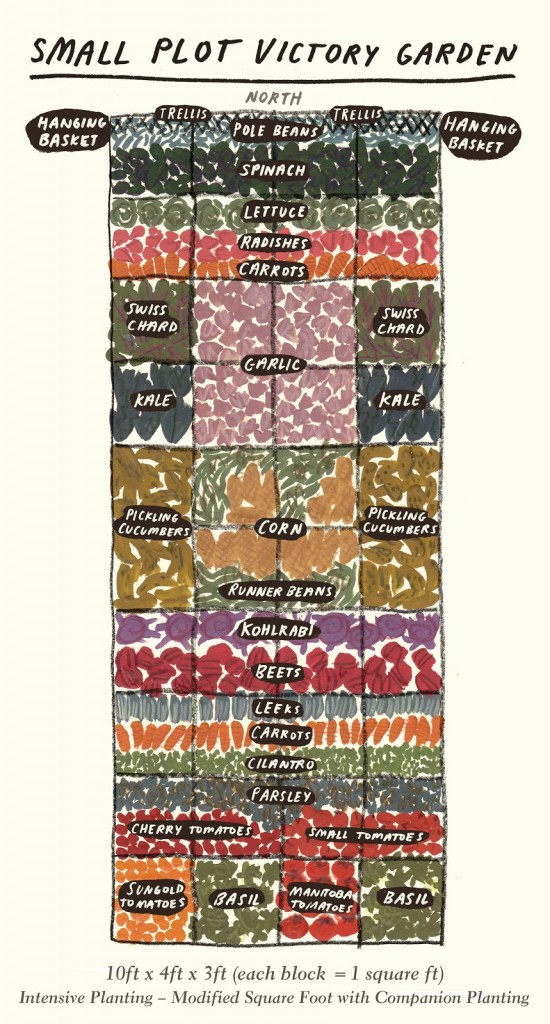

But most of us don’t have yards big enough to support the big vegetable gardens of the first half of the 20th century. Our gardens this time around will be grown in smaller plots in our yards, community gardens, or on the boulevard. They’ll be grown in potagers, raised beds, hanging baskets, vertical walls, and patio containers. We might even take over a perennial bed or two. These spaces will be planted intensively, and we will get our seeds and soil online and from local businesses still able to provide the essentials.

We’ve updated the victory garden of the past to reflect today’s compact urban gardens and smaller family units (click here for printable illustration and legend). Although space may be at a premium, there are many ways to maximize yields and grow a wide diversity of edibles using tried-and-true techniques. Think vertical by growing vegetables such as zucchini, indeterminate tomatoes, and pole beans on trellises. Square foot gardening–instead of traditional row planting–is a huge space optimizer. Succession planting and intercropping give you the opportunity to fast-grow plant crops one after another in the same space, or adjacent.

We’ve updated the victory garden of the past to reflect today’s compact urban gardens and smaller family units (click here for printable illustration and legend). Although space may be at a premium, there are many ways to maximize yields and grow a wide diversity of edibles using tried-and-true techniques. Think vertical by growing vegetables such as zucchini, indeterminate tomatoes, and pole beans on trellises. Square foot gardening–instead of traditional row planting–is a huge space optimizer. Succession planting and intercropping give you the opportunity to fast-grow plant crops one after another in the same space, or adjacent.

We can help prevent the spread of pests and diseases by practicing Integrated Pest Management, a concept victory gardeners would not likely have known by name. Monitoring crops for any signs of trouble and taking the action that is least harmful to the environment to control problems is a positive approach that supports healthier ecosystems.

Unlike the original growers of victory gardens, Canadians now have access to a welcome diversity of edible plants, easily obtainable from a huge number of national seed companies and greenhouses. We’re no longer stuck with only one or two varieties of each crop—we can choose from a huge range the ones that are perfect for our growing regions, our plot size, and our family’s palates.

Today, victory gardens are back—not because our government is encouraging us to plant them, but as a grassroots movement. It is borne out of our need to be empowered in this time of anxiety. And just like previous generations, we too can contribute to the effort to defeat a common enemy that threatens our world. We can grow for food security, for self-sufficiency in a society built on inter-dependency, to learn new skills, and to develop a passion for gardening and all it provides us.

Gardening is therapeutic, connecting us to Earth and the spirit of community that binds us all. To grow our own food, even a bit, is to be in control rather than helpless. It calms us, engages us, and gives so much back in return.

—–

Janet Melrose and Sheryl Normandeau are the authors of the Guides for the Prairie Gardener series, available now

—–

Credits

- Illustrated by Tree Abraham

- Garden Plan by Janet Melrose and Sheryl Normandeau, authors of the Guides for the Prairie Gardeners series

Vintage image sources

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/victory-gardens

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/victory-gardens-editorial

References

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/victory-gardens

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victory_garden

- https://www.vancourier.com/news/worried-about-covid-19-plant-a-victory-garden-1.24109793

- https://prism.ucalgary.ca/bitstream/handle/1880/110196/9781773850917_chapter11.pdf?sequence=13&isAllowed=y

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/25/dining/victory-gardens-coronavirus.html

- https://slate.com/human-interest/2020/04/victory-garden-coronavirus-wwii-history.html